After many anxious months, the import permit was approved, and to this day I remember unboxing the gun for the first time. My initial impression was that Heym must have made a mistake and shipped the wrong gun as the gun was so slim and light that it had to be a lighter calibre and not a .450. I checked the calibre engraving, and it was indeed a .450 NE. I had certainly made the right choice of calibre!

Back home, I couldn’t wait to test-fire the gun, and I had some left-over ammo from the Army & Navy. At the range, this unfortunately didn’t work out quite so well. The Army & Navy was an old gun and had been regulated with cordite-loaded ammunition, and for regulation I had used S335 in it. The Heym shot these at around 2 250 fps, but the shots from the left and right barrels were crossing. Problems!

Having read my friend Graeme Wright’s excellent book on double rifles, I was well-versed in what was needed to regulate the Heym. I initially reduced the loads to 2 150 fps, but this made no difference. I knew that the ammunition used to regulate the Heym was Hornady factory ammunition, and the powder used would be something like H4350. The South African equivalent was S365, so I gave this a go. The first load I tried was 92 grains, but the velocity was 2 350 fps with the left and right barrels still crossing. I reduced the load to 88 grains and two shots from the left and right barrels printed neatly into one ragged hole. The muzzle velocity was also an extremely pleasing 2 250 fps with a Dzombo 480-grain solid.

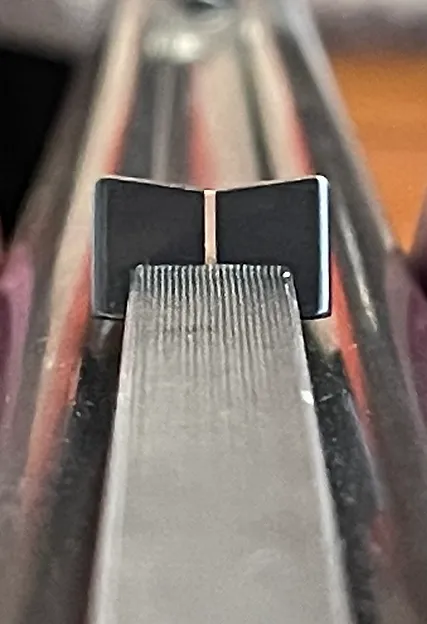

It was at this time that I started testing 500-grain Dzombo solids, and I found that with the same load, the Heym also shot both barrels into one hole at 25 metres at a velocity of 2 200 fps. Preferring heavier bullets, this was the load I settled on. The gun shot slightly high with the 500-grain load, but some careful filing of the rear V-sight sight solved this, and suddenly I was in business. I also filed the face of the brass bead flat and then worked the angle slightly forward off the vertical. The bead now picks up more light and stands out very clearly.

Over the next few months, I found that when shooting fast I lost my grip, and when pulling the back trigger, I was getting cut on my trigger finger by the front trigger. This had never happened with the Army &Navy, and I realised that the Heym’s grip was not as slim as that of the old English double rifle, and that this was probably what was causing the problems: my grip on the slimmer Army & Navy stock was a lot stronger. I also determined that the beavertail fore-end made little difference in protecting my hand when the barrels heated up. It did, however, prevent me from grabbing the barrels which reduced the fast handling and pointability of the gun. The English definitely designed their rifles the right way!

To solve these issues, stockmaker Faan de Vos reshaped and refinished the stock, slimming the grip, and converting the beavertail to a splinter fore-end. He also changed the chequering from sharp to flat-top, another huge advantage. Faan also fitted a new Silver’s recoil pad with rounded edges. I prefer old-style English recoil pads made from urethane (as opposed to pure rubber) as they are less tacky and don’t snag on your clothing when the gun is shouldered or lowered. I also polished the recoil pad with furniture wax to make it even smoother. The finishing of a recoil pad is an often-neglected aspect. Have a look at most shotguns and you will find that the recoil pad or butt-plate is smooth with no sharp edges. This ensures that the gun doesn’t snag in the shoulder when mounted. By rounding and polishing a urethane pad, the same effect can be achieved.

Recently, I made a few more modifications to the rifle, namely the sights.

As one gets older it is inevitable that one’s eyesight deteriorates. With that comes the inability to focus on the rear V-sight. I visited Danie Joubert, and we discussed the cutting of a new V sight that was slightly wider and with a V cut at a very shallow angle, still keeping the silver centre line. The finished version worked well for very close shots, but my eyes still battled to centre the bead perfectly, which is imperative as the shots get longer.

At this stage, I started using a reflex sight with a red dot that I had originally ordered with the gun. I have used red-dot sights on other rifles for close to 15 years now, and I was aware of the advantages that they have over iron sights. I would say that at anything over 15 yards there is an absolute advantage of the red dot sight. It’s only at the very short range that “the jury is still out” in my opinion. It’s at these distances that one is usually in an extreme hurry and there is no time or possibility to focus on sights and then an incoming target. Here one shoots where you look, and hence the absolute necessity of a well-fitting stock. When shooting in this manner, having less in the way on top of the barrel is the advantage.

After using the red dot for a while, I became increasingly more convinced that this was the way to go, so I started experimenting with various mounting options to get the sight mounted as low over the barrels as possible to get the best fit with the stock that had been cut for use with iron sights.

Having used Aimpoint red dot sights extensively I also started exploring options to mount an Aimpoint, instead of the reflex sight. In my opinion, Aimpoint red dot sights are in a league of their own, for the following reasons:

They are parallax free which basically means that once sighted in, wherever the dot is in the sight window, this is where the bullet goes. This is a real advantage on longer shots, and it also enables you to shoot accurately even if the dot is in the bottom of the sight window (a real factor especially if you stock was cut with drop at comb for iron sights);

They have the longest battery life, so can be left on all the time, and only change the battery every year or two so there is absolutely no risk of failure;

The sight is sealed which means it works more reliably in harsh conditions especially where rain and mud are involved;

The optics glass is the clearest of all I have tested;

Lastly, they are the most robust red dot sights. I have exposed them to huge hardship and have never had one fail me.

I have used the Aimpoint Micro H-2 a lot and it works very well. But for the double rifle, it looked like I would be able to mount an Aimpoint Acro C-2 a little bit lower, so that is what I ended up buying. A master gunsmith and good friend from Sweden, PO Stenmark, kindly sourced me a base for the sight and custom machined it to fit on the rib. When the base arrived, Danie Joubert did the final fitment. I could not be happier with the finished product. And as you can see from the photos, it is right on top of the rib, the base is hardly visible.

One important note is where on the rib to fit the sight. One doesn’t want it in the way of where you hold the rifle, and it must also not get in the way when loading rounds fast.

To finish off, I would like to discuss another important topic: ammunition. It is after all the bullet that actually does the work. In over 28 years, I have extensively tested many types of solids and soft-point big-bore bullets. Concerning solids, I exclusively use flat-point bullets and their variants. From the many tests that friends and I have conducted over the years, it was shown time and again that they out-penetrate equivalent-weight round-nose solids and also make a substantially larger wound channel.

Because of this, I used nothing but the South African-made Dzombo monometal solids for 17 years. The Dzombo solid is excellent, it is not only the right shape for maximum penetration but is turned from a brass alloy that is the strongest construction for a solid. Added to this, the Dzombo has a superb bearing-surface design and pressure build-up is much lower compared to other bullets I have used. I can therefore achieve slightly higher velocities at lower pressure with the Dzombos.

Recently I started using the Woodleigh Hydrostatically Stabilised Solids, commonly known as “Hydro’s”. From tests that Graeme Wright did in Australia, the Woodleigh Hydro is the best “brush busting” bullet available. It deviates less when a branch or some other obstacle is inadvertently in the way. I have also found Hydro’s to make the largest and most destructive wound channel of any solid I have used. So far, they also seem to penetrate the same distance as a Dzombo solid. I remove the plastic caps that are fitted specifically for feeding in bolt action rifles, as these are not necessary, and don’t help to load a double rifle any faster. The bearing surface also works well, and I achieve the same velocity for a load as I do with the equivalent weight Dzombo solid.

For soft-points I prefer solid-shank, bonded-core designs, and I’ve found the North Fork to be the best. I prefer them because if all else fails and the bullet breaks up, you are still left with a solid (albeit a slightly lighter one). Next best are the partition types such as Swift’s A-Frame. I also like a round or large blunt nose as opposed to a sharp spitzer in a soft point intended for dangerous game as I have found that they expand faster and more reliably. The North Fork bullets also have a bearing-surface design like the Dzombo and one can also achieve slightly higher velocities at lower pressure with them. I believe the North Fork PP is in a league of its own on cats, as the grooves cut close to the tip facilitate very fast expansion. Unfortunately, North Fork are no longer easily available, so I have switched to Swift A-Frame’s.

The finished product of my double rifle and the diet that it is fed represents to me the epitome of fine handling and reliability. It is indeed a heavy rifle that one can rely upon when you find yourself in the thick stuff and the chips are down.