Overwhelmed by the sheer number of bleeding soldiers at the Battle of Metz in 1793, a French military surgeon was forced to develop a rapid classification system to determine which of the wounded troops needed treatment most urgently.

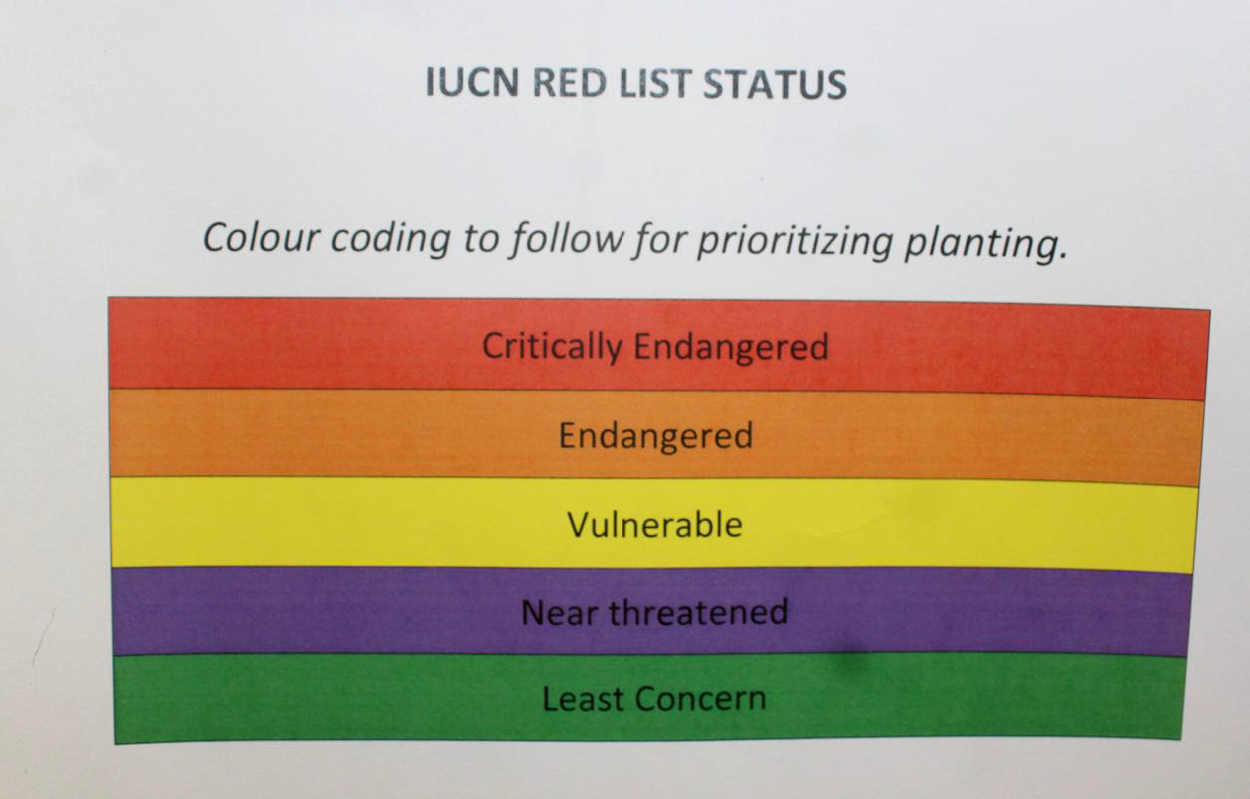

More than 200 years later, the triage system developed by Baron Dominique Larrey during the Napoleonic wars is being used locally to stem the casualty list of some of South Africa’s most threatened succulent plant species.

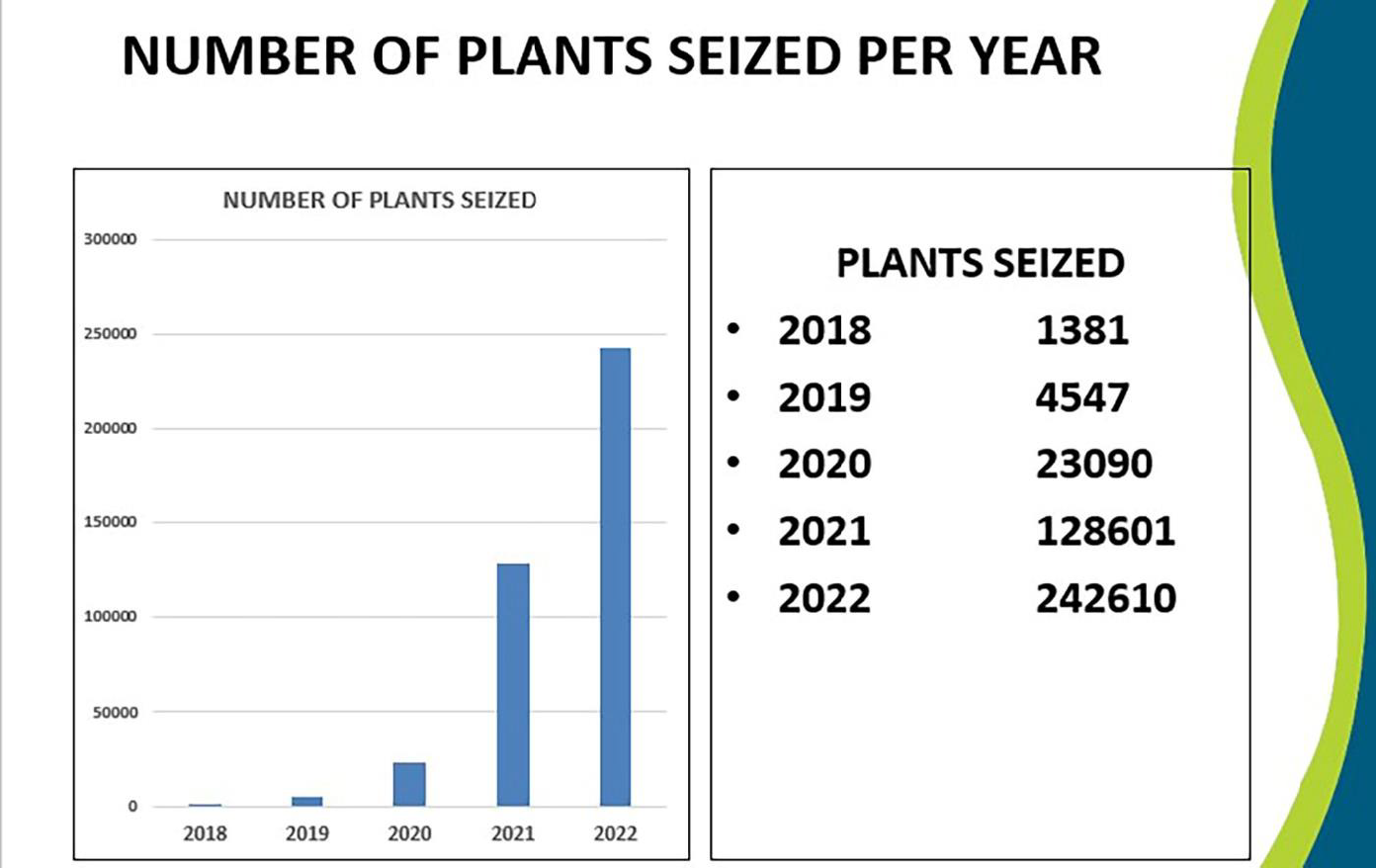

“We have been getting between three and seven plant confiscation cases coming in every week, mostly from the Northern Cape – and the number of plants in each case can vary between 1,000 and 10,000 plants,” says Dr Carina Becker du Toit, a senior botanical scientist at the sharp end of rescue operations for confiscated succulent plants in the Western Cape and Northern Cape.