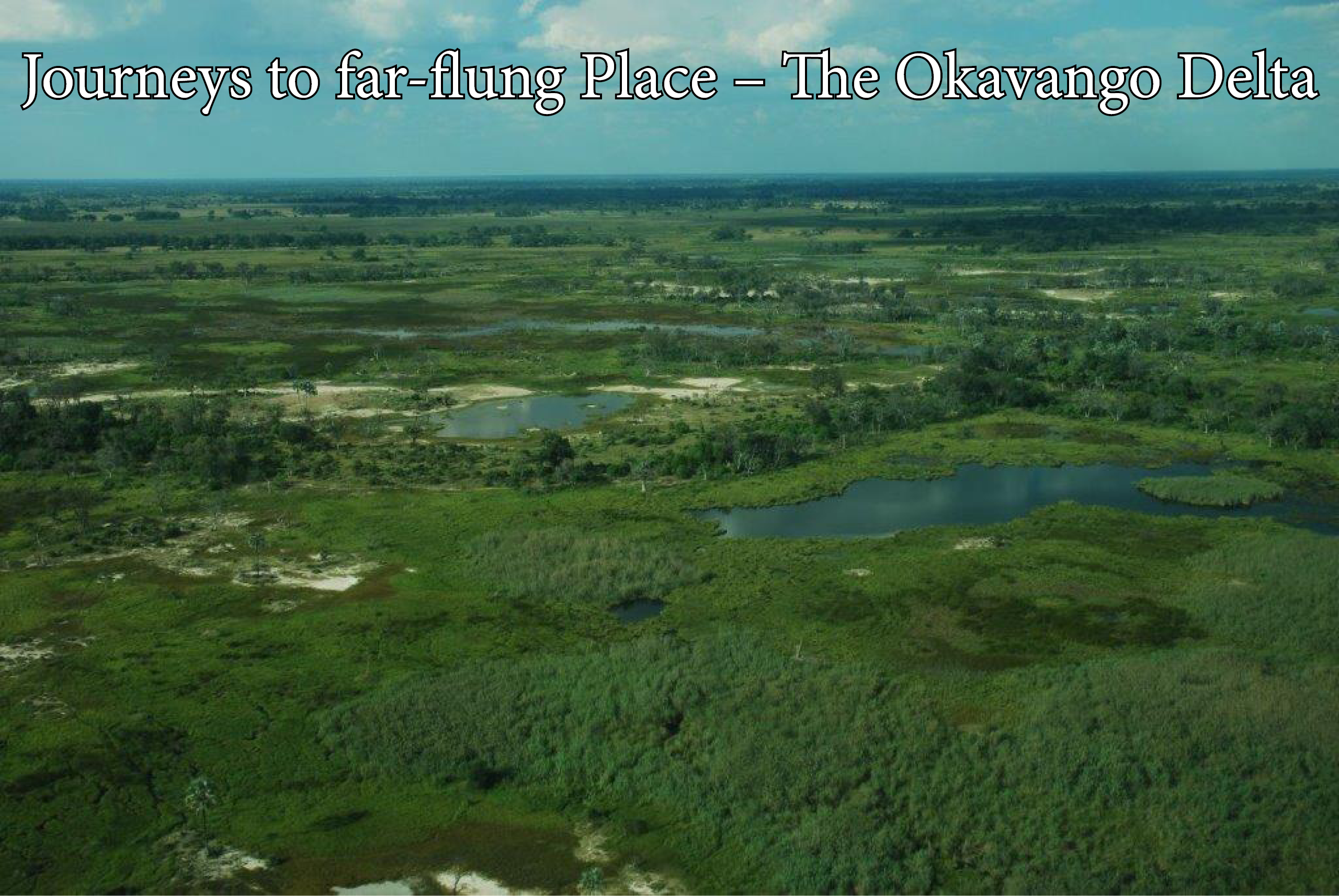

I was fortunate to spend time with various graduate students who did their research in the Okavango Delta System which is a natural wonder at the southern end of the Great Rift Valley of Africa. Some 2 million years ago, the Okavango River which starts as a trickle in the Highlands of Angola flowed through northern Botswana to drain into the Greater Makgadikgadi Lake that mostly dried up some 11 000 years ago. When a severe earthquake occurred near the current border of Botswana with Namibia 50 000 years ago, it uplifted the land to form a tectonic trough filled with Kalahari sand which blocked the southward flow of the river and formed the swampy, inland Okavango Delta which covers a surface area of 250 by 150 km. It is named after the Okovango (Kavango people) of northern Namibia who settled there.

Every year the seasonal flooding of the Okavango River from January to February spreads some 11 km3 of water which enters the delta from March to June. The flood peaks from June to August when the delta swells to three times its permanent size and attracts one of Africa’s greatest concentrations of wildlife. Some of the water still drains into Lake Ngami where it eventually evaporates or is transpired by the vegetation. When the water levels gradually recede, some water remains in major canals, riverbeds, waterholes and a number of larger lagoons which attract large numbers of wildlife.

Rafts of papyrus Cyperus papyrus and the common reed Phragmites australis form a large part of the Okavango’s vegetation. During the flood season they float well above the sandy riverbed with their roots dangling in the water. The waters of the Okavango River contain almost no mud and these plants capture the sand and create new islands on which more plants take root. The gap between riverbed and roots is used as shelter by the Nile crocodile Crocodylus niloticus.

Hippopotamus trails through the vegetation create new channels and ultimately new long, thin and often curved islands in the gently meandering rivers and are the natural banks of old river channels which have become blocked by plants and the deposition of sand. Due to the flatness of the delta and the large tonnage of sand flowing into it from the Okavango River the floor of the delta is constantly rising slowly. Where channels are today, islands will be tomorrow while new channels may wash away the existing islands. It is projected that the Okovango Delta will experience decreasing annual rainfall and increasing temperatures as a result of global warming which are likely to reduce its size.

About 70 percent of the islands began as termite mounds where a tree rooted on a mound of soil. The agglomeration of salt around the plant roots creates barren, white patches in the centre of many of the islands. Chief’s Island, the largest island in the delta, was formed by a geological fault line which uplifted an area of over 70 km long and 15 km wide. Historically it was the exclusive hunting area for the chief but is now a protected area of wildlife which provides a core refuge for much of the resident wildlife when the waters rise.

When my graduate student Russell Biggs studied the ecology of Chief’s Island for his MSc dissertation in the late 1970s, I visited him occasionally at his camp on Chief’s Island. These visits required an odd mix of modern and ancient travel as we left Pretoria to fly to Maun on the southern edge of the Delta with a light aircraft. After clearing immigration at Maun airport, one of the busiest airports for light aircraft in Africa, we flew to another island near Chief’s Island where we landed at the bush landing strip of a Ker, Downey and Selby Safari lodge.

From the bush landing strip we were transported individually to Russell’s camp on Chief’s Island with makoros which are commonly used as a form of transport in the Okavango Delta and on the Chobe River in Botswana. A makoro is traditionally made by excavating the trunk of a large, straight tree but is increasingly being made of fibre-glass to the advantage of the preservation of more of the large endangered trees. They are a practical means of transport for the local residents when they move around the swamp. We moved at a leisurely pace through the swamplands and it took us as long to cover the last few kilometres as it had to fly to the swamp from Pretoria, but peace and quiet had suddenly replaced our hurried life.

At the camp I stayed in a tent which was set up a little distance away from a tall and shady sausage tree Kigelia africana. I wondered why the tent was not closer to the trunk of the tree but it soon became clear when one of the large fruit pods dropped to the ground. These pods which can be up to 1 m long and 180 mm in diameter and weigh up to 10 kg will easily penetrate the canvas of a tent and injure any person on which it drops. From the camp we roamed through various channels and were amazed at the crystal-clear water which allowed us to see to the bottom. When we explored Chief’s Island, we were vigilant for the lions which rest in the shade by day and soon learned not wear dark clothes to avoid being targeted by the swarms of tsetse flies.